Seismo Blog

Which Fault Is It?

Categories: Bay Area | Earthquake Faults and Faulting | West Napa Fault

August 24, 2014

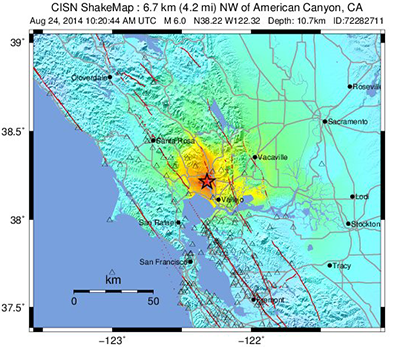

It was at 3:20 am early Sunday morning when tens of thousands of Bay Area residents woke up to an ominous rumbling under their beds. In the deep darkness of the night, the vibrations of the strongest earthquake in the Bay Area since the Loma Prieta Quake of 1989 made their way through our region. They were noticed as far south as Fresno and as far north as Chico. But nowhere else was it felt more strongly than in the City of Napa, and the southern parts of Napa and Sonoma Counties and westernmost Solano County. The epicenter of this magnitude 6.0 temblor lay halfway between Napa and Vallejo, almost 7 miles below the Napa County Airport. And strong it was indeed: The seismic station closest to the epicenter registered shaking of almost a half of a "g" at a distance of merely 2 miles, where "g" is the common unit for measuring ground acceleration in terms of the static gravitational g-pull of the Earth itself.

In Napa, just 6 miles northwest of the epicenter, the shaking let chimneys and brick facades collapse and glass windows burst. In wine cellars, stores and restaurants thousands of bottles of wine jumped off the shelves, spilling hundreds of gallons of the prized liquid on floors and carpets. Because the earthquake also ruptured gas lines, several fires broke out in Napa - the worst one consumed four trailers in a mobile home park on Orchard Avenue. As of early Sunday morning, almost 90 people were reported injured, mostly with cuts and bruises, but three people were admitted to hospitals in serious condition.

With its extensive network of seismic stations in the area, seismologists at the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory on Campus and at the USGS in Menlo Park were able to pinpoint the focus of the earthquake exactly to within one tenth of a mile. But despite such high precision, they were not able to determine on which fault the big temblor had occurred. Such uncertainty is not the scientists' fault. While the location of some faults in the Bay Area can easily be mapped, such as the Hayward fault along the foothills of the East Bay or the San Andreas Fault on the Peninsula, the faults north of San Pablo Bay are much more difficult to decipher. The reason why the location of Sunday's quake could not be pinned to a fault is the fact that faults are usually mapped by their expression on the surface. The curbs distorted by the creeping Hayward Fault in Berkeley and Hayward allow scientist to locate the fault to within inches. But faults do not leave such telltale traces in the loose soil of the epicentral area of Sunday's quake. There the sediments of the Napa River meet the mushy ground of the salt marshes of San Pablo Bay. In fact, experts from the California Geologic Survey - a State office - recently tried to map possible faults in the area, but found no conclusive evidence. For researchers, however, this quake was a blessing in disguise. Mapping the exact location of the aftershocks in three dimensions will yield a picture of the actual fault plane underground. Once these shocks are properly recorded and analyzed, it will be seen if the USGS was correct to initially assign the quake to the widely unknown West Napa Fault. (hra093)

BSL Blogging Team: Who we are

Recent Posts

-

: Alerts for the Whole West Coast

-

: Destruction in the Eastern Aegean Sea

-

: An Explosion in Beirut heard all over the Middle East

View Posts By Location

Categories

- Alaska (3)

- Bay Area (24)

- Buildings (3)

- Calaveras (4)

- California (13)

- California ShakeOut (3)

- Central California (4)

- Chile (4)

- Earthquake Early Warning (10)

- Earthquake Faults and Faulting (44)

- Earthquake Science (3)

- Haiti (3)

- Hayward (12)

- Indonesia (4)

- Induced Seismicity (3)

- Instrumentation (18)

- Italy (6)

- Japan (7)

- MOBB (3)

- Mendocino Triple Junction (5)

- Mexico (7)

- Nepal (3)

- North Korea (5)

- Nuclear Test (5)

- Ocean Bottom Seismometer (3)

- Oklahoma (4)

- Plate Tectonics (18)

- Preparedness, Risks, and Hazards (16)

- Salton Sea (3)

- San Andreas Fault (14)

- Seismic Waves (13)

- Seismograms (4)

- ShakeAlert (3)

- Southern California (5)

- Surface Waves (3)

- Today in Earthquake History (20)

- Volcanoes (4)

- subduction (3)