Seismo Blog

Quakes on Mars?

Categories: Mars

May 3, 2018

When engineers from the Berkeley Seismological Laboratory set out to install a new seismic monitoring station in Northern California, their task is relatively straightforward. Once a landowner has agreed to support Earth science by hosting a new station, a suitable location needs to be found on the land in question. This being achieved, the engineers will dig a hole, install in it a seismometer with some protective insulation around it, set up solar panels to power everything, and install a mast to host a telecommunications antenna. This job is usually done in a few days and costs between ten and twenty thousand dollars.

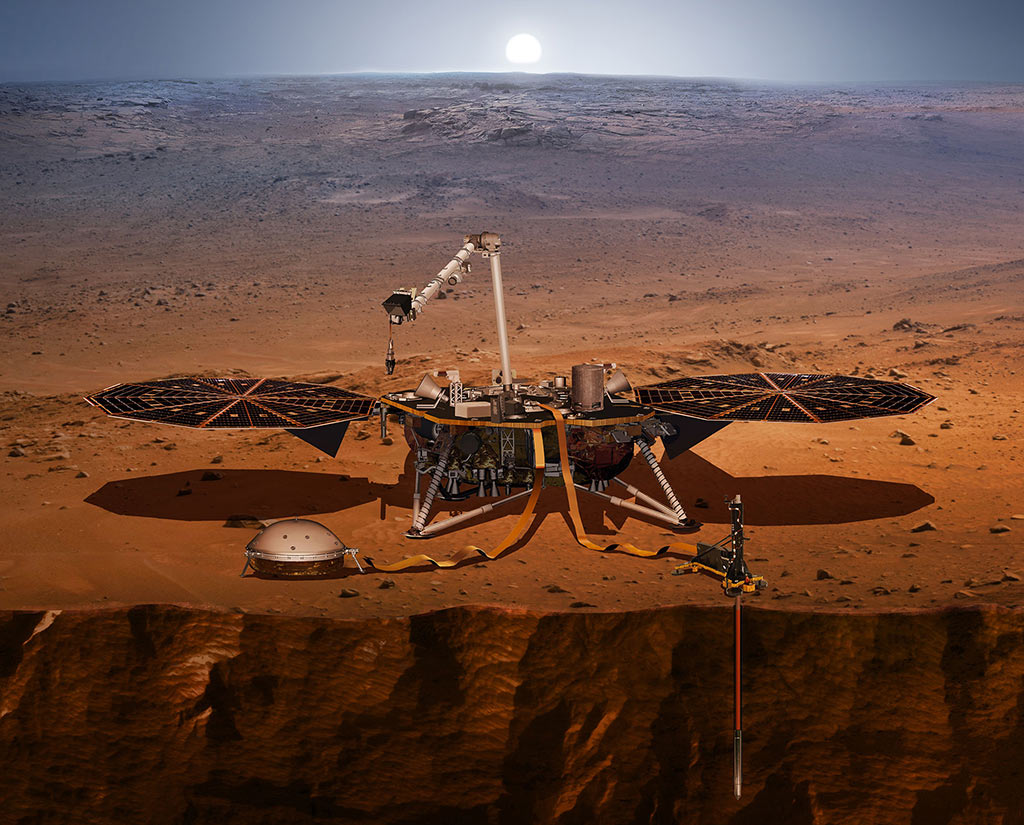

Figure 1: If all goes well the Insight-Lander could touch down on the surface of Mars around Thanksgiving. This artist rendering, shows the the lander after the root arm has deployed the seismometer (left) and a small drill rig (right), which will sink a thermoprobe about 15 feet into the ground. (Illustration: NASA)

However, when Philippe Lognonné wants to install a seismic station, he has to go through many, many more hoops and spend hundreds of millions of dollars. And all that, while he is completely uncertain that he will even measure anything resembling a quake. The Professor in Geophysics and Planetary Science from the University of Paris Diderot is the principal investigator for a unique scientific experiment, which will be launched into space this Saturday. He and his international group of collaborators want to measure quakes on Mars.

This team is part of Nasa's Insight Mission, which — if all goes well during the launch and the following 300 million mile journey — will put a lander on the Red Planet by Thanksgiving. The goal is to investigate the interior of Mars. Hardly anything is known about what's deep inside our neighbor in the solar system, although Mars has been studied via spacecraft flybys, orbiters and the spectacular travels of rolling robots for more than 50 years.

Lognonné hopes that this will change as soon as the lander's robot arm will have installed the seismometer on the plain "Elysium Planitia" in the equatorial region of the Red Planet. If marsquakes do indeed exist, their seismic waves will illuminate the planet's interior similar to the X-rays used in medical diagnostics to probe the human body. Such seismic imaging is standard practice for seismologists when they investigate the interior of the Earth. The discovery that the core deep within the Earth has two parts, a molten outer core and a solid center, was one of this method's greatest successes. The inner core was found by the Danish Seismologist Inge Lehmann 80 years ago.

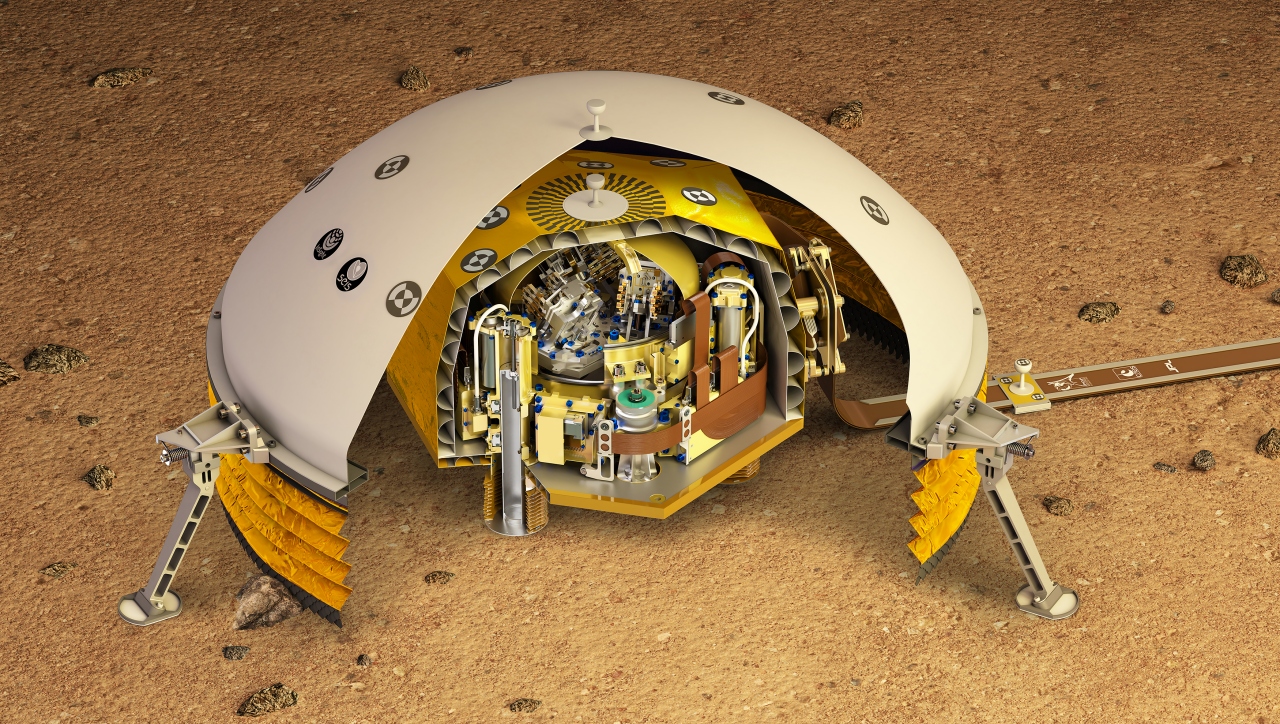

Figure 2: A cut-through illustration of the Mars seismometer. The actual sensors are protected from the elements by a dome and a thermal shield. Illustration: IPGP)

Why are scientists unsure that the Red Planet has quakes similar to Earth? The driving force for most earthquakes is the restless motion of the lithospheric plates, which make up the dynamic puzzle of the Earth's surface. Currently we have no indication that similar plate tectonics processes move the surface of Mars as well. There are however, large structures on Mars which look like tectonic basins. The biggest of them is "Valles Marineris," a huge Grand Canyon almost the size of the lower 48 states. If this basin is still tectonically active, it should generate quakes which in turn will generate seismic waves.

And what good is the seismometer when there are no quakes on Mars? Its deployment will not be in vain, because Mars is located on the inner edge of the asteroid belt. That means it is hit by space rocks more often than Earth. In addition, its thinner atmosphere allows smaller asteroids to make it all the way to the ground, so even something the size of a basketball can slam into the surface intact. This probably happens a few times a month on the Red Planet. And every time a meteorite impacts, it generates a set of seismic waves in Mars' crust, which can be recorded by the seismometer.

If all goes well, Mars will only be the second extraterrestrial body to have its own seismic station. During the Apollo Missions five decades ago astronauts deployed a network of seismometers on the Moon. Those instruments recorded about 10,000 moonquakes and 2000 meteorite impacts. Applying seismic imaging techniques to the collected data, scientists deciphered the structure of the moon's interior. It has a crust about three times a thick as the Earth's. Below it is the large lunar mantle. In the center is a small core with a diameter of about 200 miles. Like the Earth's core it contains two parts, a fluid outer layer engulfing a solid interior. (hra154)

BSL Blogging Team: Who we are

Recent Posts

-

: Alerts for the Whole West Coast

-

: Destruction in the Eastern Aegean Sea

-

: An Explosion in Beirut heard all over the Middle East

View Posts By Location

Categories

- Alaska (3)

- Bay Area (24)

- Buildings (3)

- Calaveras (4)

- California (13)

- California ShakeOut (3)

- Central California (4)

- Chile (4)

- Earthquake Early Warning (10)

- Earthquake Faults and Faulting (44)

- Earthquake Science (3)

- Haiti (3)

- Hayward (12)

- Indonesia (4)

- Induced Seismicity (3)

- Instrumentation (18)

- Italy (6)

- Japan (7)

- MOBB (3)

- Mendocino Triple Junction (5)

- Mexico (7)

- Nepal (3)

- North Korea (5)

- Nuclear Test (5)

- Ocean Bottom Seismometer (3)

- Oklahoma (4)

- Plate Tectonics (18)

- Preparedness, Risks, and Hazards (16)

- Salton Sea (3)

- San Andreas Fault (14)

- Seismic Waves (13)

- Seismograms (4)

- ShakeAlert (3)

- Southern California (5)

- Surface Waves (3)

- Today in Earthquake History (20)

- Volcanoes (4)

- subduction (3)