Seismo Blog

Burned by the Ring of Fire

Categories: Japan | Ecuador | Induced Earthquake | Ring of Fire | Preparedness, Risks, and Hazards

April 17, 2016

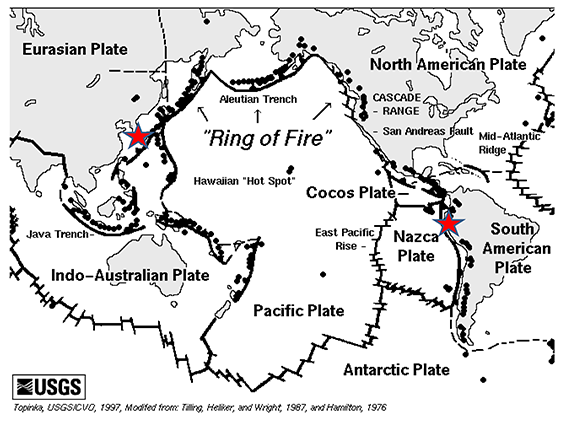

The complex Ring of Fire around the Pacific Ocean. The two red stars mark the locations of the recent earthquakes in Japan and Ecuador.

In his 1963 hit song "The Ring of Fire" Johnny Cash sang prosaically about love and how it "burns, burns, burns" when you fall "down, down, down and the flames went higher." Little did the late icon of country music know that more than half a century later, the term "Ring of Fire" would have become one of the most abused and misunderstood phrases when laymen talk about the Earth and its inner rumblings. This weekend is a typical example. When journalists from all over the world interviewed seismologists one question invariably come up: Are the earthquake sequence on the Japanese island of Kyushu and the 7.8 quake which struck coastal Ecuador on Saturday night (local time) related? Even the venerable BBC fell into the trap by noting in one of its news bulletins, that after all, "both regions are located on the same fault line, the Pacific Ring of Fire."

Let's make two points very clear from the start:

1. There is no physical cause and effect relationship between the recent quakes in Japan and the ones in northern South America, and

2. the Pacific Ring of Fire is not a faultline.

Why then, one needs to ask, is there such a gap between public perception about distant earthquakes and geophysical reality? For an answer let us look at the Ring of Fire first.

The red dots on this map show the locations of the 7.8 earthquake in northwestern Ecuador and its aftershocks. The dots in other colors mark previous, unrelated quakes. (Click to view larger.) Source: Geophysical Institute, National Polytechnic University, Quito.

There is no doubt that the Pacific Rim is one of the tectonically most active areas in the world. Nearly all of the great earthquakes occur along this circumpacific belt, which is also dotted with hundreds of active volcanoes. Unfortunately, most people stop there. They see this impressive arc on the map and make broad connections. However, if one looks at the Pacific Rim in more detail from a geotectonics point of view, one will quickly see how versatile it is. It is not a uniform fault line like the Hayward fault in the blogger's backyard, but an extremely complex puzzle of many tectonic plates and and their interactions.

Take the section along the west coast of North America for instance. Starting along the coast of northern British Columbia in Canada and ending at California's Cape Mendocino, we have a subduction zone. There it is not the Pacific Plate which dives under the American Plate but the small Juan-de-Fuca Plate. This zone produces very strong quakes and is indeed dotted with the volcanoes of the Cascade Mountains. Between Cape Mendocino and the Salton Sea in southern California, the San Andreas Fault represents the location of the Ring of Fire. This fault produces earthquakes of a very different kind than the subduction zone further north and does not have any associated volcanoes. South of the US-Mexican border, the Ring of Fire is dominated by a spreading zone located in the Gulf of California. There the plate boundary becomes divergent: The Baja California peninsula is slowly being ripped away from the Mexican mainland. There is no physical or tectonic connection between these three different interactions of tectonics plates except in the small areas where they merge into each other. Similar versatility can be found all along the Pacific Rim.

And what about the other question: Could the ongoing earthquake series in southern Japan have triggered the much stronger quake at the coast of Ecuador? First of all, none of these quakes occurred on the Pacific Plate. As explained in yesterday's blog, the quake sequence in Kyushu took place along the boundary between the Philippine and the Eurasian plates. The quake in Ecuador was generated in a subduction zone, where the Nazca plate dives beneath the South American continent.

In addition, these quakes are almost as far apart as you can get on the globe. Their respective epicenters are almost 10,000 miles apart. Despite the distance, the sensitive seismometers operated by the Geophysical Institute of the National Polytechnic University in Ecuador's capital Quito registered the strongest of the Kyushu quakes with a magnitude of 7. And sensitive they needed to be indeed: The maximum amplitude of the ground movement in Ecuador caused by the Japan quake was nearly 50 micrometers per second, which corresponds to about half of the diameter of a human hair. The mechanical stress induced in the earth by such a tiny ground movement is far too small to kick-off a large earthquake.

After all, Saturday's quake in Ecuador with its magnitude 7.8 caused the ground in Berkeley to move by about 240 micrometers per second. Although this is five times stronger, the Hayward Fault which runs through Berkeley and is currently under a heavy tectonic load, did not go off. (hra119)

BSL Blogging Team: Who we are

Recent Posts

-

: Alerts for the Whole West Coast

-

: Destruction in the Eastern Aegean Sea

-

: An Explosion in Beirut heard all over the Middle East

View Posts By Location

Categories

- Alaska (3)

- Bay Area (24)

- Buildings (3)

- Calaveras (4)

- California (13)

- California ShakeOut (3)

- Central California (4)

- Chile (4)

- Earthquake Early Warning (10)

- Earthquake Faults and Faulting (44)

- Earthquake Science (3)

- Haiti (3)

- Hayward (12)

- Indonesia (4)

- Induced Seismicity (3)

- Instrumentation (18)

- Italy (6)

- Japan (7)

- MOBB (3)

- Mendocino Triple Junction (5)

- Mexico (7)

- Nepal (3)

- North Korea (5)

- Nuclear Test (5)

- Ocean Bottom Seismometer (3)

- Oklahoma (4)

- Plate Tectonics (18)

- Preparedness, Risks, and Hazards (16)

- Salton Sea (3)

- San Andreas Fault (14)

- Seismic Waves (13)

- Seismograms (4)

- ShakeAlert (3)

- Southern California (5)

- Surface Waves (3)

- Today in Earthquake History (20)

- Volcanoes (4)

- subduction (3)