Seismo Blog

When the Ground Gives Way

Categories: Liquefaction | Preparedness, Risks, and Hazards

September 24, 2008

Everybody has probably done it while frolicking at the beach: Stand with both feet on the wet sand and move your body quickly up and down several times without lifting your feet. After a short while the ground gives way. You sink a few inches into the sand and you might even lose your balance. Well, you just simulated one of the most dangerous effects seismic waves can have on buildings: Soil liquefaction.

Figure 1: Mud boils caused by liquefaction (From the Karl V. Steinbrugge Collection, Earthquake Engineering Research Center, UC Berkeley). (Click to view larger image.)

How can soil, which is hard enough for you to walk on, lose its strength and stiffness just because it is shaken a little bit? The secret is the water in the soil. Liquefaction occurs only in soils in which the space between individual sand particles is completely filled with water. Such soils are called "water saturated". The water exerts pressure on the particles, which in turn determines how tightly they are packed together. Before an earthquake, the water pressure is low and static. During the dynamic shaking, however, the water pressure can increase so much that the particles can move freely past each other. Once that happens, the soil loses its strength and becomes a gooey, slippery liquid.

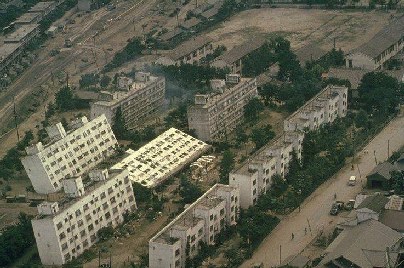

Figure 2: Building tilted due to liquefaction caused by the Niigata, Japan, earthquake in 1964 (From the Karl V. Steinbrugge Collection, Earthquake Engineering Research Center, UC Berkeley). (Click to view larger image.)

"Sand boils" are a relatively harmless consequence of such liquefaction; they look like small mud volcanoes (Figure 1). The overpressure inside the soil causes the sand to squirt out like lava from a volcanic crater. However, when soil liquefaction occurs under a building, it may sink into the soil, like your feet did during your experiment at the beach. The building might even tip over.

The first time seismologists fully recognized the devastating effects of soil liquefaction was in 1964. During an earthquake under Niigata in Japan several apartment buildings sank into the ground and tipped over, because the water saturated soil on which they were built liquefied (Figure 2). The Bay Area is by no means immune to liquefaction, because many buildings in low lying areas are built on soils saturated with water from the Bay. Liquefaction can occur in all areas shaded brown and yellow in the map in Figure 3. The Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) has published a booklet with detailed information about the hazards of liquefaction in our region.(hra005)

BSL Blogging Team: Who we are

Recent Posts

-

: Alerts for the Whole West Coast

-

: Destruction in the Eastern Aegean Sea

-

: An Explosion in Beirut heard all over the Middle East

View Posts By Location

Categories

- Alaska (3)

- Bay Area (24)

- Buildings (3)

- Calaveras (4)

- California (13)

- Central California (4)

- Chile (4)

- Earthquake Early Warning (10)

- Earthquake Faults and Faulting (44)

- Earthquake Science (3)

- Haiti (3)

- Hayward (12)

- Indonesia (4)

- Induced Seismicity (3)

- Instrumentation (18)

- Italy (6)

- Japan (7)

- MOBB (3)

- Mendocino Triple Junction (5)

- Mexico (7)

- Nepal (3)

- North Korea (5)

- Nuclear Test (5)

- Ocean Bottom Seismometer (3)

- Oklahoma (4)

- Plate Tectonics (18)

- Preparedness, Risks, and Hazards (15)

- Salton Sea (3)

- San Andreas Fault (14)

- Seismic Waves (13)

- Seismograms (4)

- ShakeAlert (3)

- Southern California (5)

- Surface Waves (3)

- Today in Earthquake History (20)

- Volcanoes (4)

- subduction (3)