Seismo Blog

A Tectonic Drag Race

Categories: Japan | Japan Trench | Plate Tectonics

March 16, 2011

Every textbook about Earth Science tells you that the giant lithospheric plates move past each other at a velocity of a few inches per year. The most common metaphor is that their speed compares directly to the rate at which a fingernail grows. That sounds gentle, harmless, and most of all manageable. Unfortunately, these numbers are utterly misleading, because they are very long term averages measured over hundreds or even thousands of years. When you look at plate movement in the short term, you recognize a completely different picture. Most of the time, nothing happens at all. The plates are tightly locked against each other, snapping perhaps in a few small earthquakes here or there. This tectonic inactivity gives us, the residents of earthquake zones, a false sense of security. Because suddenly, within a fraction of a second and without any warning, the geologic interlocking may fail and then all hell breaks loose. The mechanical energy, caused by the constant push of the churning viscous mantle below and stored in the plates over hundreds of years, is released. In a few seconds the plates jump past each other by dozens of yards. In many respects, the plate movement is like the fate of a drag racing car. Most of time, the machine sits around idly, but once in a while, its engine is fired up and the dragster races a few hundred yards at lightning speed.

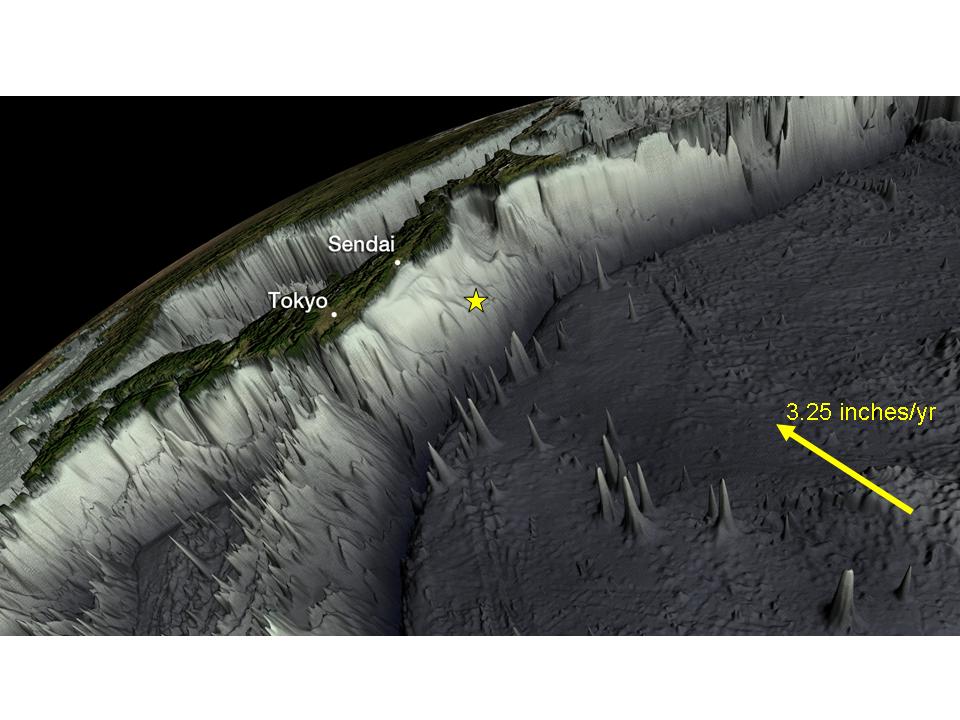

Figure 1: If you took away the water of the Northwestern Pacific, this is how the sea floor would look. In its move westward, the Pacific Plate slams into what looks like a wall. This is the Eastern edge of the Eurasian Plate. The yellow star denotes the location of the epicenter. (Source: NOAA)

This is what happened last Friday off the east coast of Honshu. When the westward moving Pacific Plate finally unlocked itself from the Eurasian Plate, the result was the giant earthquake. Over the long term the Pacific and Eurasian Plates drift past each at an average rate of about 3.25 inches per year. But on Friday, they raced passed each other by dozens of yards in about two minutes.

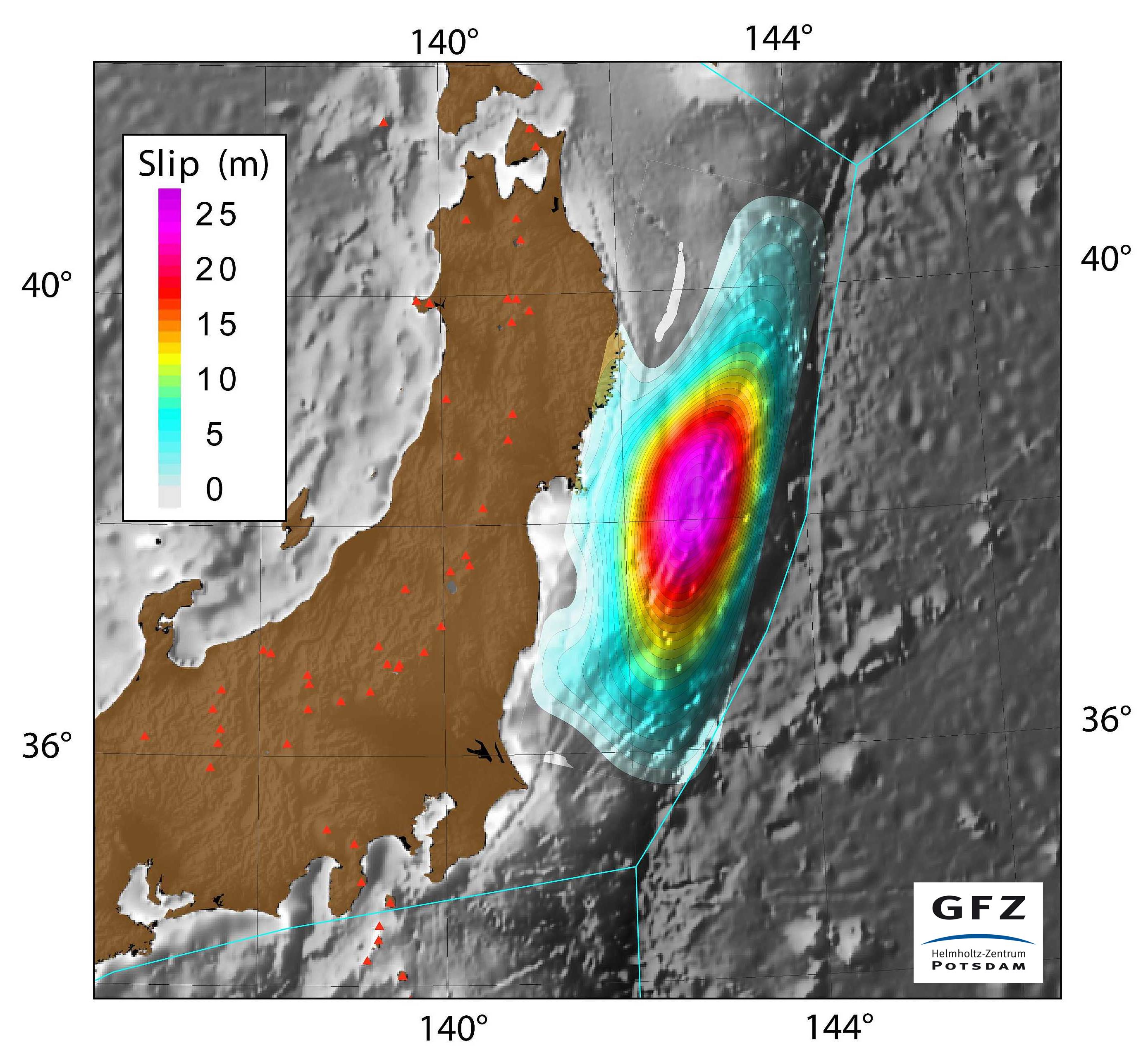

Several researchers have already made models of how the interlocking between the plates actually failed, the quake's so called "rupture process". Gavin Hayes from the USGS office in Golden, CO, used the recordings of 60 seismic stations from all over the globe to compute the rupture. According to (his calculations) the rupture area underground was almost 200 miles long and 125 miles wide. Imagine, the entire state of West Virginia slipping up to 20 yards eastwards in less than two minutes.

Figure 2: The rupture region (colored area) of Friday's quake may have been as large as the state of West Virginia. At the center of the area, the plates may have jumped passed each other by more than 25 meters. (Source: GFZ-Potsdam. Click to view larger image.)

A group of scientists from the Geoforschungszentrum in Potsdam, Germany, used the recordings of almost 500 sensitive GPS-stations in Japan to model the rupture. Their calculations yielded a 250 mile long zone with a offset of almost 28 yards (see Figure 2). Researchers from Harvard University used several hundred earthquake stations on the US mainland for their calculations and came to similar conclusions. They estimate the rupture to be 240 miles long by 150 miles across. They even simulated how the rupture spread over this area (see their animation).

In the meantime, the massive temblor has been given a name, and the magnitude of the "Great Tohoku Earthquake" has officially been upgraded to 9.0. (hra063)

BSL Blogging Team: Who we are

Recent Posts

-

: Alerts for the Whole West Coast

-

: Destruction in the Eastern Aegean Sea

-

: An Explosion in Beirut heard all over the Middle East

View Posts By Location

Categories

- Alaska (3)

- Bay Area (24)

- Buildings (3)

- Calaveras (4)

- California (13)

- Central California (4)

- Chile (4)

- Earthquake Early Warning (10)

- Earthquake Faults and Faulting (44)

- Earthquake Science (3)

- Haiti (3)

- Hayward (12)

- Indonesia (4)

- Induced Seismicity (3)

- Instrumentation (18)

- Italy (6)

- Japan (7)

- MOBB (3)

- Mendocino Triple Junction (5)

- Mexico (7)

- Nepal (3)

- North Korea (5)

- Nuclear Test (5)

- Ocean Bottom Seismometer (3)

- Oklahoma (4)

- Plate Tectonics (18)

- Preparedness, Risks, and Hazards (15)

- Salton Sea (3)

- San Andreas Fault (14)

- Seismic Waves (13)

- Seismograms (4)

- ShakeAlert (3)

- Southern California (5)

- Surface Waves (3)

- Today in Earthquake History (20)

- Volcanoes (4)

- subduction (3)